William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray

Born William Makepeace Thackeray

18 July 1811 (1811-07-18)

Calcutta, India

Died 24 December 1863 (1863-12-25)

London, England

Occupation Novelist

Nationality English

Period 1829–1864 (published posthumously)

Genres Historical Fiction

Notable work(s)Vanity Fair

Spouse(s) Isabella Gethin Shawe

Influences

John Bunyan

Influenced

George Orwell, Charlotte Brontë

William Makepeace Thackeray (pronounced /ˈθækəri/; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was an English novelist of the 19th century. He was famous for his satirical works, particularly Vanity Fair, a panoramic portrait of English society.

Born William Makepeace Thackeray

18 July 1811 (1811-07-18)

Calcutta, India

Died 24 December 1863 (1863-12-25)

London, England

Occupation Novelist

Nationality English

Period 1829–1864 (published posthumously)

Genres Historical Fiction

Notable work(s)Vanity Fair

Spouse(s) Isabella Gethin Shawe

Influences

John Bunyan

Influenced

George Orwell, Charlotte Brontë

William Makepeace Thackeray (pronounced /ˈθækəri/; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was an English novelist of the 19th century. He was famous for his satirical works, particularly Vanity Fair, a panoramic portrait of English society.

Contents

1 Biography

1 Biography

2 Works

3 Family life and background

4 Reputation and legacy

5 See also

6 List of works

7 References

8 Notes

9 External links

Biography

Thackeray, an only child, was born in Calcutta, India, where his father, Richmond Thackeray (1 September 1781 – 13 September 1815), held the high rank of secretary to the board of revenue in the British East India Company. His mother, Anne Becher (1792–1864) was the second daughter of Harriet and John Harman Becher who was also a secretary (writer) for the East India Company.

William's father died in 1815, which caused his mother to decide to return William to England in 1816 (she remained in India). The ship on which he traveled made a short stopover at St. Helena where the imprisoned Napoleon was pointed out to him. Once in England he was educated at schools in Southampton and Chiswick and then at Charterhouse School, where he was a close friend of John Leech. He disliked Charterhouse,[1] parodying it in his later fiction as "Slaughterhouse." (Nevertheless Thackeray was honored in the Charterhouse Chapel with a monument after his death.) Illness in his last year there (during which he reportedly grew to his full height of 6'3") postponed his matriculation at Trinity College, Cambridge, until February 1829. Never too keen on academic studies, he left the University in 1830, though some of his earliest writing appeared in university publications The Snob and The Gownsman.[2]

He travelled for some time on the continent, visiting Paris and Weimar, where he met Goethe. He returned to England and began to study law at the Middle Temple, but soon gave that up. On reaching the age of 21 he came into his inheritance but he squandered much of it on gambling and by funding two unsuccessful newspapers, The National Standard and The Constitutional for which he had hoped to write. He also lost a good part of his fortune in the collapse of two Indian banks. Forced to consider a profession to support himself, he turned first to art, which he studied in Paris, but did not pursue it except in later years as the illustrator of some of his own novels and other writings.

Thackeray, an only child, was born in Calcutta, India, where his father, Richmond Thackeray (1 September 1781 – 13 September 1815), held the high rank of secretary to the board of revenue in the British East India Company. His mother, Anne Becher (1792–1864) was the second daughter of Harriet and John Harman Becher who was also a secretary (writer) for the East India Company.

William's father died in 1815, which caused his mother to decide to return William to England in 1816 (she remained in India). The ship on which he traveled made a short stopover at St. Helena where the imprisoned Napoleon was pointed out to him. Once in England he was educated at schools in Southampton and Chiswick and then at Charterhouse School, where he was a close friend of John Leech. He disliked Charterhouse,[1] parodying it in his later fiction as "Slaughterhouse." (Nevertheless Thackeray was honored in the Charterhouse Chapel with a monument after his death.) Illness in his last year there (during which he reportedly grew to his full height of 6'3") postponed his matriculation at Trinity College, Cambridge, until February 1829. Never too keen on academic studies, he left the University in 1830, though some of his earliest writing appeared in university publications The Snob and The Gownsman.[2]

He travelled for some time on the continent, visiting Paris and Weimar, where he met Goethe. He returned to England and began to study law at the Middle Temple, but soon gave that up. On reaching the age of 21 he came into his inheritance but he squandered much of it on gambling and by funding two unsuccessful newspapers, The National Standard and The Constitutional for which he had hoped to write. He also lost a good part of his fortune in the collapse of two Indian banks. Forced to consider a profession to support himself, he turned first to art, which he studied in Paris, but did not pursue it except in later years as the illustrator of some of his own novels and other writings.

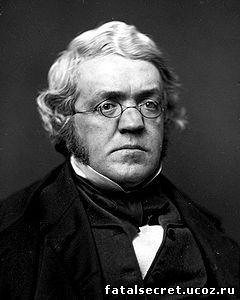

Thackeray portrayed by Eyre Crowe, 1845

Thackeray's years of semi-idleness ended after he met and, on 20 August 1836, married Isabella Gethin Shawe (1816–1893), second daughter of Matthew Shawe, a colonel, who had died after extraordinary service, primarily in India, and his wife, Isabella Creagh. Their three daughters were Anne Isabella (1837–1919), Jane (died at 8 months) and Harriet Marian (1840–1875). He now began "writing for his life," as he put it, turning to journalism in an effort to support his young family.

He primarily worked for Fraser's Magazine, a sharp-witted and sharp-tongued conservative publication, for which he produced art criticism, short fictional sketches, and two longer fictional works, Catherine and The Luck of Barry Lyndon. Later, through his connection to the illustrator John Leech, he began writing for the newly created Punch magazine, where he published The Snob Papers, later collected as The Book of Snobs. This work popularized the modern meaning of the word "snob".

Tragedy struck in his personal life as his wife succumbed to depression after the birth of their third child in 1840. Finding he could get no work done at home, he spent more and more time away, until September of that year, when he noticed how grave her condition was. Struck by guilt, he took his ailing wife to Ireland. During the crossing she threw herself from a water-closet into the sea, from which she was rescued. They fled back home after a four-week domestic battle with her mother. From November 1840 to February 1842 she was in and out of professional care, her condition waxing and waning.

Thackeray's years of semi-idleness ended after he met and, on 20 August 1836, married Isabella Gethin Shawe (1816–1893), second daughter of Matthew Shawe, a colonel, who had died after extraordinary service, primarily in India, and his wife, Isabella Creagh. Their three daughters were Anne Isabella (1837–1919), Jane (died at 8 months) and Harriet Marian (1840–1875). He now began "writing for his life," as he put it, turning to journalism in an effort to support his young family.

He primarily worked for Fraser's Magazine, a sharp-witted and sharp-tongued conservative publication, for which he produced art criticism, short fictional sketches, and two longer fictional works, Catherine and The Luck of Barry Lyndon. Later, through his connection to the illustrator John Leech, he began writing for the newly created Punch magazine, where he published The Snob Papers, later collected as The Book of Snobs. This work popularized the modern meaning of the word "snob".

Tragedy struck in his personal life as his wife succumbed to depression after the birth of their third child in 1840. Finding he could get no work done at home, he spent more and more time away, until September of that year, when he noticed how grave her condition was. Struck by guilt, he took his ailing wife to Ireland. During the crossing she threw herself from a water-closet into the sea, from which she was rescued. They fled back home after a four-week domestic battle with her mother. From November 1840 to February 1842 she was in and out of professional care, her condition waxing and waning.

Caricature of Thackeray by Thackeray

In the long run, she deteriorated into a permanent state of detachment from reality, unaware of the world around her. Thackeray desperately sought cures for her, but nothing worked, and she ended up confined in a home near Paris. She remained there until 1893, outliving her husband by thirty years. After his wife's illness, Thackeray became a de facto widower, never establishing another permanent relationship. He did pursue other women, in particular Mrs. Jane Brookfield and Sally Baxter. In 1851 Mr. Brookfield barred Thackeray from further visits to or correspondence with Jane. Baxter, an American twenty years his junior whom he met during a lecture tour in New York City in 1852, married another man in 1855.

In the early 1840s, Thackeray had some success with two travel books, The Paris Sketch Book and The Irish Sketch Book. Later in the decade, he achieved some notoriety with his Snob Papers, but the work that really established his fame was the novel Vanity Fair, which first appeared in serialized instalments beginning in January 1847. Even before Vanity Fair completed its serial run, Thackeray had become a celebrity, sought after by the very lords and ladies he satirized; they hailed him as the equal of Dickens.

He remained "at the top of the tree", as he put it, for the remaining decade and a half of his life, producing several large novels, notably Pendennis, The Newcomes, and The History of Henry Esmond, despite various illnesses, including a near fatal one that struck him in 1849 in the middle of writing Pendennis. He twice visited the United States on lecture tours during this period.

In the long run, she deteriorated into a permanent state of detachment from reality, unaware of the world around her. Thackeray desperately sought cures for her, but nothing worked, and she ended up confined in a home near Paris. She remained there until 1893, outliving her husband by thirty years. After his wife's illness, Thackeray became a de facto widower, never establishing another permanent relationship. He did pursue other women, in particular Mrs. Jane Brookfield and Sally Baxter. In 1851 Mr. Brookfield barred Thackeray from further visits to or correspondence with Jane. Baxter, an American twenty years his junior whom he met during a lecture tour in New York City in 1852, married another man in 1855.

In the early 1840s, Thackeray had some success with two travel books, The Paris Sketch Book and The Irish Sketch Book. Later in the decade, he achieved some notoriety with his Snob Papers, but the work that really established his fame was the novel Vanity Fair, which first appeared in serialized instalments beginning in January 1847. Even before Vanity Fair completed its serial run, Thackeray had become a celebrity, sought after by the very lords and ladies he satirized; they hailed him as the equal of Dickens.

He remained "at the top of the tree", as he put it, for the remaining decade and a half of his life, producing several large novels, notably Pendennis, The Newcomes, and The History of Henry Esmond, despite various illnesses, including a near fatal one that struck him in 1849 in the middle of writing Pendennis. He twice visited the United States on lecture tours during this period.

Thackeray

Thackeray also gave lectures in London on the English humourists of the eighteenth century, and on the first four Hanoverian monarchs. The latter series was published in book form as The Four Georges. In Oxford, he stood unsuccessfully as an independent for Parliament. He was narrowly beaten by Cardwell (1070 votes, against 1005 for Thackeray).

In 1860, Thackeray became editor of the newly established Cornhill Magazine, but was never comfortable as an editor, preferring to contribute to the magazine as a columnist, producing his Roundabout Papers for it.

His health worsened during the 1850s and he was plagued by the recurring stricture of the urethra that laid him up for days at a time. He also felt he had lost much of his creative impetus. He worsened matters by over-eating and drinking and avoiding exercise, though he enjoyed horseback riding and kept a horse. He could not break his addiction to spicy peppers, further ruining his digestion. On 23 December 1863, after returning from dining out and before dressing for bed, Thackeray suffered a stroke and was found dead on his bed in the morning. His death at the age of fifty-two was entirely unexpected, and shocked his family, friends, and reading public. An estimated 7000 people attended his funeral at Kensington Gardens. He was buried on 29 December at Kensal Green Cemetery, and a memorial bust sculpted by Marochetti can be found in Westminster Abbey.

Thackeray also gave lectures in London on the English humourists of the eighteenth century, and on the first four Hanoverian monarchs. The latter series was published in book form as The Four Georges. In Oxford, he stood unsuccessfully as an independent for Parliament. He was narrowly beaten by Cardwell (1070 votes, against 1005 for Thackeray).

In 1860, Thackeray became editor of the newly established Cornhill Magazine, but was never comfortable as an editor, preferring to contribute to the magazine as a columnist, producing his Roundabout Papers for it.

His health worsened during the 1850s and he was plagued by the recurring stricture of the urethra that laid him up for days at a time. He also felt he had lost much of his creative impetus. He worsened matters by over-eating and drinking and avoiding exercise, though he enjoyed horseback riding and kept a horse. He could not break his addiction to spicy peppers, further ruining his digestion. On 23 December 1863, after returning from dining out and before dressing for bed, Thackeray suffered a stroke and was found dead on his bed in the morning. His death at the age of fifty-two was entirely unexpected, and shocked his family, friends, and reading public. An estimated 7000 people attended his funeral at Kensington Gardens. He was buried on 29 December at Kensal Green Cemetery, and a memorial bust sculpted by Marochetti can be found in Westminster Abbey.

Works

Thackeray began as a satirist and parodist,writing papers with a sneaking fondness for roguish upstarts like Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair, Barry Lyndon in The Luck of Barry Lyndon and Catherine in Catherine. In his earliest works, writing under such pseudonyms as Charles James Yellowplush, Michael Angelo Titmarsh and George Savage Fitz-Boodle, he tended towards the savage in his attacks on high society, military prowess, the institution of marriage and hypocrisy.

Thackeray began as a satirist and parodist,writing papers with a sneaking fondness for roguish upstarts like Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair, Barry Lyndon in The Luck of Barry Lyndon and Catherine in Catherine. In his earliest works, writing under such pseudonyms as Charles James Yellowplush, Michael Angelo Titmarsh and George Savage Fitz-Boodle, he tended towards the savage in his attacks on high society, military prowess, the institution of marriage and hypocrisy.

Title-page to Vanity Fair, drawn by Thackeray,

who furnished the illustrations for many of his earlier editions.

One of his very earliest works, "Timbuctoo" (1829), contained his burlesque upon the subject set for the Cambridge Chancellor's medal for English verse, (the contest was won by Tennyson with "Timbuctoo"). His writing career really began with a series of satirical sketches now usually known as The Yellowplush Papers, which appeared in Fraser's Magazine beginning in 1837. These were adapted for BBC Radio 4 in 2009, with Adam Buxton playing Charles Yellowplush.[3]

Between May 1839 and February 1840, Fraser's published the work sometimes considered Thackeray's first novel, Catherine, originally intended as a satire of the Newgate school of crime fiction but ending up more as a rollicking picaresque tale in its own right.

In The Luck of Barry Lyndon, a novel serialized in Fraser's in 1844, Thackeray explored the situation of an outsider trying to achieve status in high society, a theme he developed much more successfully in Vanity Fair with the character of Becky Sharp, the artist's daughter who rises nearly to the heights by manipulating the other characters.

He is best known now for Vanity Fair, with its deft skewerings of human foibles and its roguishly attractive heroine. His large novels from the period after this, once described unflatteringly by Henry James as examples of "loose baggy monsters", have faded from view, perhaps because they reflect a mellowing in the author, who became so successful with his satires on society that he seemed to lose his zest for attacking it.

The later works include Pendennis, a sort of bildungsroman depicting the coming of age of Arthur Pendennis, a kind of alter ego of Thackeray's who also features as the narrator of two later novels: The Newcomes and The Adventures of Philip. The Newcomes is noteworthy for its critical portrayal of the "marriage market", while Philip is noteworthy for its semi-autobiographical look back at Thackeray's early life, in which the author partially regains some of his early satirical zest.

Also notable among the later novels is The History of Henry Esmond, in which Thackeray tried to write a novel in the style of the eighteenth century. In fact, the eighteenth century held a great appeal for Thackeray. Not only Esmond but also Barry Lyndon and Catherine are set then, as is the sequel to Esmond, The Virginians, which takes place in America and includes George Washington as a character who nearly kills one of the protagonists in a duel.

One of his very earliest works, "Timbuctoo" (1829), contained his burlesque upon the subject set for the Cambridge Chancellor's medal for English verse, (the contest was won by Tennyson with "Timbuctoo"). His writing career really began with a series of satirical sketches now usually known as The Yellowplush Papers, which appeared in Fraser's Magazine beginning in 1837. These were adapted for BBC Radio 4 in 2009, with Adam Buxton playing Charles Yellowplush.[3]

Between May 1839 and February 1840, Fraser's published the work sometimes considered Thackeray's first novel, Catherine, originally intended as a satire of the Newgate school of crime fiction but ending up more as a rollicking picaresque tale in its own right.

In The Luck of Barry Lyndon, a novel serialized in Fraser's in 1844, Thackeray explored the situation of an outsider trying to achieve status in high society, a theme he developed much more successfully in Vanity Fair with the character of Becky Sharp, the artist's daughter who rises nearly to the heights by manipulating the other characters.

He is best known now for Vanity Fair, with its deft skewerings of human foibles and its roguishly attractive heroine. His large novels from the period after this, once described unflatteringly by Henry James as examples of "loose baggy monsters", have faded from view, perhaps because they reflect a mellowing in the author, who became so successful with his satires on society that he seemed to lose his zest for attacking it.

The later works include Pendennis, a sort of bildungsroman depicting the coming of age of Arthur Pendennis, a kind of alter ego of Thackeray's who also features as the narrator of two later novels: The Newcomes and The Adventures of Philip. The Newcomes is noteworthy for its critical portrayal of the "marriage market", while Philip is noteworthy for its semi-autobiographical look back at Thackeray's early life, in which the author partially regains some of his early satirical zest.

Also notable among the later novels is The History of Henry Esmond, in which Thackeray tried to write a novel in the style of the eighteenth century. In fact, the eighteenth century held a great appeal for Thackeray. Not only Esmond but also Barry Lyndon and Catherine are set then, as is the sequel to Esmond, The Virginians, which takes place in America and includes George Washington as a character who nearly kills one of the protagonists in a duel.

Family life and background

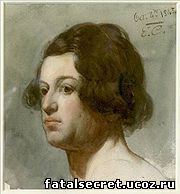

Anne Becher and William Makepeace Thackeray, c.1813

Thackeray's father, Richmond, was born at South Mimms and went to India in 1798 at the age of sixteen to assume his duties as writer (secretary) with the East India Company. Richmond fathered a daughter, Sarah Redfield, born in 1804, by Charlotte Sophia Rudd, his native and possibly Eurasian mistress, the mother and daughter being named in his will. Such liaisons were common among gentlemen of the East India Company, and it formed no bar to his later courting and marrying William's mother.[4]

Anne Becher, born 1792, was "one of the reigning beauties of the day", a daughter of John Harmon Becher (Collector of the South 24 Parganas district d. Calcutta, 1800), of an old Bengal civilian family "noted for the tenderness of its women". Anne Becher, her sister Harriet and widowed mother Harriet had been sent back to India by her authoritarian guardian grandmother, widow Ann Becher, in 1809 on the Earl Howe. Anne's grandmother had told her that the man she loved, Henry Carmichael-Smyth, an ensign of the Bengal Engineers whom she met at an Assembly Ball in Bath, Somerset during 1807, had died, and Henry was told that Anne was no longer interested in him . This was not true. Though Carmichael-Smyth was from a distinguished Scottish military family, Anne's grandmother went to extreme lengths to thwart their marriage; surviving family letters state that she wanted a better match for her Granddaughter.[5]

Anne Becher and Richmond Thackeray were married in Calcutta on 13 October 1810. Their only child, William, was subsequently born on 18 July 1811.[6]

There was a fine miniature portrait of the exuberant and youthful Anne Becher Thackeray and William Makepeace Thackeray at about age 2, done in Madras by George Chinnery c. 1813.[7]

Her family's deception was unexpectedly revealed in 1812, when Richmond Thackeray unwittingly invited to dinner the supposedly dead Carmichael-Smyth. After Richmond's death of a fever on 13 September 1815, Anne married Henry Carmichael-Smyth on 13 March 1817, but they did not return to England until 1820, though they had sent William off to school there more than three years before. The separation from his mother had a traumatic effect on the young Thackeray which he discusses in his essay "On Letts's Diary" in The Roundabout Papers.

He is British comedian Al Murray's great-great-great-grandfather.[8]

Thackeray's father, Richmond, was born at South Mimms and went to India in 1798 at the age of sixteen to assume his duties as writer (secretary) with the East India Company. Richmond fathered a daughter, Sarah Redfield, born in 1804, by Charlotte Sophia Rudd, his native and possibly Eurasian mistress, the mother and daughter being named in his will. Such liaisons were common among gentlemen of the East India Company, and it formed no bar to his later courting and marrying William's mother.[4]

Anne Becher, born 1792, was "one of the reigning beauties of the day", a daughter of John Harmon Becher (Collector of the South 24 Parganas district d. Calcutta, 1800), of an old Bengal civilian family "noted for the tenderness of its women". Anne Becher, her sister Harriet and widowed mother Harriet had been sent back to India by her authoritarian guardian grandmother, widow Ann Becher, in 1809 on the Earl Howe. Anne's grandmother had told her that the man she loved, Henry Carmichael-Smyth, an ensign of the Bengal Engineers whom she met at an Assembly Ball in Bath, Somerset during 1807, had died, and Henry was told that Anne was no longer interested in him . This was not true. Though Carmichael-Smyth was from a distinguished Scottish military family, Anne's grandmother went to extreme lengths to thwart their marriage; surviving family letters state that she wanted a better match for her Granddaughter.[5]

Anne Becher and Richmond Thackeray were married in Calcutta on 13 October 1810. Their only child, William, was subsequently born on 18 July 1811.[6]

There was a fine miniature portrait of the exuberant and youthful Anne Becher Thackeray and William Makepeace Thackeray at about age 2, done in Madras by George Chinnery c. 1813.[7]

Her family's deception was unexpectedly revealed in 1812, when Richmond Thackeray unwittingly invited to dinner the supposedly dead Carmichael-Smyth. After Richmond's death of a fever on 13 September 1815, Anne married Henry Carmichael-Smyth on 13 March 1817, but they did not return to England until 1820, though they had sent William off to school there more than three years before. The separation from his mother had a traumatic effect on the young Thackeray which he discusses in his essay "On Letts's Diary" in The Roundabout Papers.

He is British comedian Al Murray's great-great-great-grandfather.[8]

Reputation and legacy

During the Victorian era, Thackeray was ranked second only to Charles Dickens, but he is now much less read and is known almost exclusively for Vanity Fair. In that novel he was able to satirize whole swaths of humanity while retaining a light touch. It also features his most memorable character, the engagingly roguish Becky Sharp. As a result, unlike Thackeray's other novels, it remains popular with the general reading public; it is a standard fixture in university courses and has been repeatedly adapted for movies and television.

In Thackeray's own day, some commentators, such as Anthony Trollope, ranked his History of Henry Esmond as his greatest work, perhaps because it expressed Victorian values of duty and earnestness, as did some of his other later novels. It is perhaps for this reason that they have not survived as well as Vanity Fair, which satirizes those values.

Thackeray saw himself as writing in the realistic tradition and distinguished himself from the exaggerations and sentimentality of Dickens. Some later commentators have accepted this self-evaluation and seen him as a realist, but others note his inclination to use eighteenth-century narrative techniques, such as digressions and talking to the reader, and argue that through them he frequently disrupts the illusion of reality. The school of Henry James, with its emphasis on maintaining that illusion, marked a break with Thackeray's techniques.

Though Edward Bulwer-Lytton is credited with originating the phrase "the Great Unwashed", the earliest citation of it to be found in his oeuvre is in "The Parisians" of 1872, while Thackeray used it as early as 1850 in "Pendennis", in an ironic context implying the phrase would be known to his readers.

2 Palace Green, a house built for Thackeray in the 1860s, is currently the permanent residence of the Israeli Embassy to the United Kingdom.[1]

His former home in Tunbridge Wells,Kent is now a fine dining restaurant named after the author [2]

During the Victorian era, Thackeray was ranked second only to Charles Dickens, but he is now much less read and is known almost exclusively for Vanity Fair. In that novel he was able to satirize whole swaths of humanity while retaining a light touch. It also features his most memorable character, the engagingly roguish Becky Sharp. As a result, unlike Thackeray's other novels, it remains popular with the general reading public; it is a standard fixture in university courses and has been repeatedly adapted for movies and television.

In Thackeray's own day, some commentators, such as Anthony Trollope, ranked his History of Henry Esmond as his greatest work, perhaps because it expressed Victorian values of duty and earnestness, as did some of his other later novels. It is perhaps for this reason that they have not survived as well as Vanity Fair, which satirizes those values.

Thackeray saw himself as writing in the realistic tradition and distinguished himself from the exaggerations and sentimentality of Dickens. Some later commentators have accepted this self-evaluation and seen him as a realist, but others note his inclination to use eighteenth-century narrative techniques, such as digressions and talking to the reader, and argue that through them he frequently disrupts the illusion of reality. The school of Henry James, with its emphasis on maintaining that illusion, marked a break with Thackeray's techniques.

Though Edward Bulwer-Lytton is credited with originating the phrase "the Great Unwashed", the earliest citation of it to be found in his oeuvre is in "The Parisians" of 1872, while Thackeray used it as early as 1850 in "Pendennis", in an ironic context implying the phrase would be known to his readers.

2 Palace Green, a house built for Thackeray in the 1860s, is currently the permanent residence of the Israeli Embassy to the United Kingdom.[1]

His former home in Tunbridge Wells,Kent is now a fine dining restaurant named after the author [2]

See also

Anne Isabella Thackeray Barry Lyndon, the film adaptation by Stanley Kubrick

List of works

Wikisource has original works written by or about: William Makepeace Thackeray

The Yellowplush Papers (1837) – ISBN 0-8095-9676-8 Catherine (1839–40) – ISBN 1-4065-0055-0 A Shabby Genteel Story (1840) – ISBN 1-4101-0509-1 The Irish Sketchbook (1843) – ISBN 0-86299-754-2 The Luck of Barry Lyndon (1844), filmed as Barry Lyndon by Stanley Kubrick – ISBN 0-19-283628-5 The Book of Snobs (1848), which popularised that term- ISBN 0-8095-9672-5 Vanity Fair (1848) – ISBN 0-14-062085-0 Pendennis (1848–1850) – ISBN 1-4043-8659-9 Rebecca and Rowena (1850), a parody sequel of Ivanhoe – ISBN 1-84391-018-7 The Paris Sketchbook (1852), featuring Roger Bontemps Men's Wives (1852) – ISBN 0-14-062085-1 The History of Henry Esmond (1852) – ISBN 0-14-143916-5 The Newcomes (1855) – ISBN 0-460-87495-0 The Rose and the Ring (1855) – ISBN 1-4043-2741-X The Virginians (1857–1859) – ISBN 1-4142-3952-1 The Adventures of Philip (1862) – ISBN 1-4101-0510-5 Denis Duval (1864) – ISBN 1-4191-1561-8 Sketches and Travels in London Notes of a Journey from Cornhill to Grand Cairo Stray Papers: Being Stories, Reviews, Verses, and Sketches (1821-1847) Literary Essays English Humourists Four Georges Lovel the Widower

References

Catalan, Zelma. The Politics of Irony in Thackeray’s Mature Fiction: Vanity Fair, Henry Esmond, The Newcomes. Sofia (Bulgaria), 2010, 250 pр. Sheldon Goldfarb Catherine: A Story (The Thackeray Edition). University of Michigan Press, 1999. Ferris, Ina. William Makepeace Thackeray. Boston: Twayne, 1983. Monsarrat, Ann. An Uneasy Victorian: Thackeray the Man, 1811–1863. London: Cassell, 1980. Peters, Catherine. Thackeray’s Universe: Shifting Worlds of Imagination and Reality. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. Prawer, Siegbert S.: Breeches and Metaphysics: Thackeray's German Discourse. Oxford : Legenda, 1997. Prawer, Siegbert S.: Israel at Vanity Fair: Jews and Judaism in the Writings of W. M. Thackeray. Leiden : Brill, 1992. Prawer, Siegbert S.: W. M. Thackeray's European sketch books : a study of literary and graphic portraiture. P. Lang, 2000. Ray, Gordon N. Thackeray: The Uses of Adversity, 1811–1846. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1955. Ray, Gordon N. Thackeray: The Age of Wisdom, 1847–1863. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1957. Ritchie, H.T. Thackeray and His Daughter. Harper and Brothers, 1924. Rodríguez Espinosa, Marcos (1998) Traducción y recepción como procesos de mediación cultural: 'Vanity Fair' en España. Málaga: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Málaga. Shillingsburg, Peter. William Makepeace Thackeray: A Literary Life. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001. Williams, Ioan M. Thackeray. London: Evans, 1968.

Notes

^ Dunton, Larkin (1896). The World and Its People. Silver, Burdett. p. 25. ^ Thackeray, William Makepeace in Venn, J. & J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge University Press, 10 vols, 1922–1958. ^ "The Yellowplush Papers". British Comedy Guide. http://www.comedy.org.uk/guide/radio/the_yellowplush_papers/. Retrieved 9 February 2009. ^ Menon, Anil (29 March 2006). "William Makepeace Thackeray: The Indian In The Closet". Round Dice. Anil Menon. http://yet.typepad.com/round_dice/2006/03/william_makepea.html. Retrieved 10 February 2009. ^ Alexander, Eric (2007). "Ancestry of William Thackeray". Henry Cort Father of the Iron Trade. henrycort.net. http://www.henrycort.net/hrthack.htm. Retrieved 10 February 2009. ^ Gilder, Jeannette Leonard; Joseph Benson Gilder (15 May 1897). The Critic: An Illustrated Monthly Review of Literature, Art, and Life (Original from Princeton University, Digitized 18 April 2008 ed.). Good Literature Pub. Co.. pp. 335. http://books.google.com/books?id=MTMZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PT346&lpg=PT346&dq=%22Richmond+Thackeray%22+died&source=web&ots=wUoXo_Ce50&sig=yMGjd8JuUg7p1deKfy2dblNrseM&hl=en&ei=D9SRSf-CCY-ctwe-pcTgCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=10&ct=result. ^ Ooty Well Preserved & Flourishing ^ Cavendish, Dominic (3 March 2007). "Prime time gentlemen, please". The Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/comedy/3663518/Prime-time-gentlemen-please.html.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: William Makepeace Thackeray

Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: William Makepeace Thackeray

The Thackerays in India and Some Calcutta Graves By William Wilson Hunter Works available at eBooks @ Adelaide Works by William Makepeace Thackeray at Project Gutenberg On Charity and Humor, discourse on behalf of a charitable organization Pegasus in Harness: Victorian Publishing and W. M. Thackeray by Peter L. Shillingsburg "Bluebeard's Ghost" by W. M. Thackeray (1843) PSU's Electronic Classics Series William Makepeace Thackeray site

Persondata

NAME Thackeray, William Makepeace

ALTERNATIVE NAMES

SHORT DESCRIPTION Novelist

DATE OF BIRTH 18 July 1811

PLACE OF BIRTH Calcutta, India

DATE OF DEATH 24 December 1863

PLACE OF DEATH London, England

ALTERNATIVE NAMES

SHORT DESCRIPTION Novelist

DATE OF BIRTH 18 July 1811

PLACE OF BIRTH Calcutta, India

DATE OF DEATH 24 December 1863

PLACE OF DEATH London, England

Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Makepeace_Thackeray

Categories: Victorian novelists | English novelists | Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge | Old Carthusians | English Anglicans | 1811 births | 1863 deaths | Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery

Personal tools

New features Log in / create account

Namespaces

Article Discussion

Variants

Views

Read Edit View history

Actions

Search

Search

Navigation

Main page Contents Featured content Current events Random article

Interaction

About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Contact Wikipedia Donate to Wikipedia Help

Toolbox

What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Permanent link Cite this page

Print/export

Create a book Download as PDF Printable version

Languages

Беларуская (тарашкевіца) Bosanski Български Česky Dansk Deutsch Español Esperanto Français 한국어 Հայերեն Hrvatski Italiano עברית ქართული Latina Lietuvių Magyar मराठी Nederlands 日本語 Norsk (bokmål) Piemontèis Polski Português Română Русский Slovenčina Slovenščina Српски / Srpski Srpskohrvatski / Српскохрватски Suomi Svenska Türkçe Українська اردو Tiếng Việt 中文

Personal tools

New features Log in / create account

Namespaces

Article Discussion

Variants

Views

Read Edit View history

Actions

Search

Search

Navigation

Main page Contents Featured content Current events Random article

Interaction

About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Contact Wikipedia Donate to Wikipedia Help

Toolbox

What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Permanent link Cite this page

Print/export

Create a book Download as PDF Printable version

Languages

Беларуская (тарашкевіца) Bosanski Български Česky Dansk Deutsch Español Esperanto Français 한국어 Հայերեն Hrvatski Italiano עברית ქართული Latina Lietuvių Magyar मराठी Nederlands 日本語 Norsk (bokmål) Piemontèis Polski Português Română Русский Slovenčina Slovenščina Српски / Srpski Srpskohrvatski / Српскохрватски Suomi Svenska Türkçe Українська اردو Tiếng Việt 中文

Источник: